“This is the authentic kind of peasant food and these places are where you find all the best shit. Without cheap rent and immigration you’re not going to get that melting pot where loads of new food comes through. This is where all the real shit happens.”

The real shit is, without question, the best shit. And it’s happening on an unassuming terraced side street just off Wilmslow Road. Huddled over a tightly packed table, brimming with glorious, sumac dusted, wood grilled lamb and eye wateringly fluffy, crisp naan fresh from the tandoor, Luke Cowdrey aka Luke Unabomber – one half of DJ duo The Unabombers, WorldWideFM DJ, Homoelectric & Homobloc promoter, instagram lunatic, restauranteur, raconteur and kebab connoisseur is passionately delivering a history lesson on the evolution of Rusholme’s unsurpassed grilled meat in naan scene, from the watershed opening of Rusholme Chippy in ’77 to the Kurdish alchemy of the present day, with nods to ‘70s New York, ‘80s Sheffield and The Ottoman Empire along the way.

As naan is effortlessly torn then enveloped around the delicate outer crunch of Kurdish lamb kebab and decorated with fresh parsley and chopped onions, Luke’s enthusiasm, despite now being on our third meal in little over two hours, is refusing to wane. And when the taste of Kurdistan Cafe’s offerings passes your lips, it’s not hard to see why. This is next level gear.

“With the Kurdish food, you have such an incredible combination of flavours,” begins Luke, constructing another hand sized pocket of perfection from the various plates in front of us. “The acidity of the sumac, the pickles, the parsley, hummus, tomatoes and the most amazing kebabs. I don’t think anyone touches these. Nico here is an absolute alchemist in all of this and when this place is on form, no one touches them.”

But how did we get here? How did the bright lights and baltis of the Curry Mile evolve into a haven for mind bending Middle Eastern peasant food?

What we’re gonna do right here is go back, way back…

We begin by meeting Luke outside the iconic red and yellow awning of Rusholme Chippy. A million memories of shot soaking 4am meals forever nestled within its walls, the place so many of us have promised to make good on that 9am lecture only to safely miss it by a solid five hours. Established in 1977, the self proclaimed ‘Kings of Kobeda’ were smouldering skewers of Persian lamb over charcoal and slapping homemade naan against the walls of their clay tandoor when The Curry Mile was still dominated by sit down Indian and Pakistani restaurants.

The same recipes and techniques have been passed down from chef-to-chef over the intervening four decades, solidifying the misleadingly christened Chippy as an irreplaceable Manchester icon. It is not only a stalwart of the scene but, as Luke relays to us, a trendsetter more than 40 years ahead of it’s time.

“Rusholme Chippy was a really early beginning of the clay oven and the tandoor. Two Persian brothers, in 1977, set it up. It’s name is deceptive. You can get chips, but they were the early adopters of what is now ubiquitous in Rusholme and a lot of Northern towns, where you have this Persian, Kurdish alchemy of kobeda and tandoor bread.

“In 1977 they had the first clay oven outside of London in the whole of the UK. They were so ahead of their time, no one really realised what we had because there weren’t any others. It didn’t really develop into anything.

“Alongside (fellow Wilmslow Rd veterans) Camel One and Abdul’s, this was where I discovered the Persian version of what became what you see now. The breads were bigger, they were more of an oval shape. Then you’ve got kobeda, which are the long lamb skewers.

“Don’t ask me how I know this, but kobeda are actually derived from the Persian swords from medieval times which they put into fires on their many escapades with the Ottoman Empire and they created a kebab in the fire. That was then taken off the skewer and put onto the bread which had been cooked in tandoor ovens.”

Seriously, fuck learning lopsided revisionist retellings of dusty old monarchs in GCSE history, get the creation of different kebab cultures on the national syllabus and get it on there now.

Pit Stop #1: Street Corner Shawarma

Our first food stop comes just over the road at Al Zain, a Kurdish owned shawarma joint serving up what Luke assures us, alongside the fellow Kurd operated Manchester Fresh Shawarma, is the best vertical Lebanese lamb in town

He’s not wrong.

The two shawarma spits (one lamb, one chicken) twirl mesmerically like ballerinas in front of you upon entrance, the much fuller chicken version a clear second best to the ludicrously popular lamb variety, crowned with tomatoes and onion, which permeate through knee tremblingly tender meat. We leave Luke to do the honours when it comes to ordering up a plethora of kebabs, all wrapped in a traditional flatbread that delivers the perfect amount of chew as we proceed to tear through our street corner starters to a cacophony of ‘fucking hell’s. The meat just glides apart, mixing effortlessly well with the bread and accompanying pickles and salad, all luminous oranges, purples and greens. The mule kick of chilli providing a welcome wake-me-up on a typically drizzly Mancunian Thursday lunchtime.

Sauce ridden smiles confirm that Luke’s almost 40 years of experience in the kebab devouring game have generated peerless instincts when it comes to identifying world class shawarma. Shout out to Lebanon too, because between this magic and their settlers in Mexico helping introduce the world to Tacos Al Pastor in the 1930’s, they have given us all two wonderful culinary gifts.

From Eighties Elephant Legs To Post-Acid House Hangouts

“Between 1985 and 2000, Pakistani and Indian versions of a kebab, which was naan bread, generally and chicken tikka arguably overtook the doner as the Holy Grail,” explains Luke.

“For me most people’s understanding of a kebab goes back to a really bad doner, an elephant leg on a skewer with pita bread and in a way it was. It’s what people had when they were pissed. Most Northern towns had doner kebabs that weren’t very good.

“A mixture of immigration and different cultures coming here opened up the whole kebab scene to more influences, so for me the defining moment was definitely Abdul’s, the Tandoori Kitchen and Camel One, which was the first wave of the Pakistani/Indian naan bread and chicken tikka and that became the standard.

“Tandoori Kitchen were actually Iranian and doing their oddball alchemy with it where they had this amazing Persian bread with incredible chicken tikka, which was the holy grail for me. But Camel One and Abdul’s were the defining places in the mid ‘80s and ‘90s. Post acid house that’s where everyone went. Camel One was the coolest hangout. All the young Asian lads and Moss Side lads came up, students came down.”

Camel One, with it’s unmistakable red and white candystriped shopfront catching the eye of anyone within at least 100 yards has, like the aforementioned Rusholme Chippy, stood the test of time, even if The Curry Mile didn’t.

The ‘Curry Mile’ moniker for Wilmslow Road was established in the 1980’s, although textile mill workers from the Indian subcontinent had been frequenting cafes in this corridor a couple of miles south of the city centre since the ‘50s. Gradually, over the next 20 years or so, the largely Pakistani community began to expand the number of restaurants along the stretch until, in the late ‘70s it was synonymous with South Asian curries.

It is no longer a name Luke feels is suitable for the area, though, given the closures of many of the original establishments and the evolution of immigration into the neighbourhood. It also could have been the blessing in disguise that saw Rusholme level up into the most exciting culinary enclave in Greater Manchester.

“The Curry Mile died on it’s arse because it changed. With the exception of Mughli, which is wonderful, a lot of the curry houses shut down and the white middle classes stopped coming to Rusholme, but that’s when the magic happened, because the next wave of immigration was Kurdish, Turkish, Afghani, Syrian, all the various elements of the Middle East.

“So the food in Rusholme, almost by osmosis slowly began to change and on the side streets you got places like Kurdistan Cafe, because of cheap rent and empty properties, which meant that new school immigrants, new arrivals, came in and could rent places for fuck all. The food was for them, it wasn’t for us, it wasn’t for tourists. It’s why this is still so cheap, it was like a return to the 60s, 70s and 80s when the Indians, Pakistanis and Bengalis on the Curry Mile would cook home curries for their people because they were working in mills, in textiles and the rag trade and those places were where they ate.

“When I arrived in Manchester it was still quite underground, places like Shazan and a few others didn’t serve alcohol, didn’t have cutlery, so it’s almost returned to that period where now instead of Indian, Pakistani and Bengali it’s Kurdish, Afghani and Syrian. So this is the next wave and this all happened under the nose of everyone. No one noticed it.”

This modern influence from the Middle East is undeniable. Wherever you look on Wilmslow Road and it’s numerous offshoots, there are menus displaying prices for kobeda, fatayer and qabuli pulao. Backstreet Kurdish bakers are slinging flatbreads four-for-a-pound while Iraqi shawarma houses sandwich their fillings on fresh Samoon bread. The aforementioned white middle classes no longer being prominent in the area has leant itself to an underground vibrancy being developed that is completely alien to anything you could ever wish to experience in the centre of town. It feels vital and enriching. Affordable, authentic street food at every turn without the merest hint of the words ‘artisan’ or ‘market’? Yes fucking please.

Pit Stop #2: Double Kobeda With a Side of Rubicon and Noughties Spanish Football

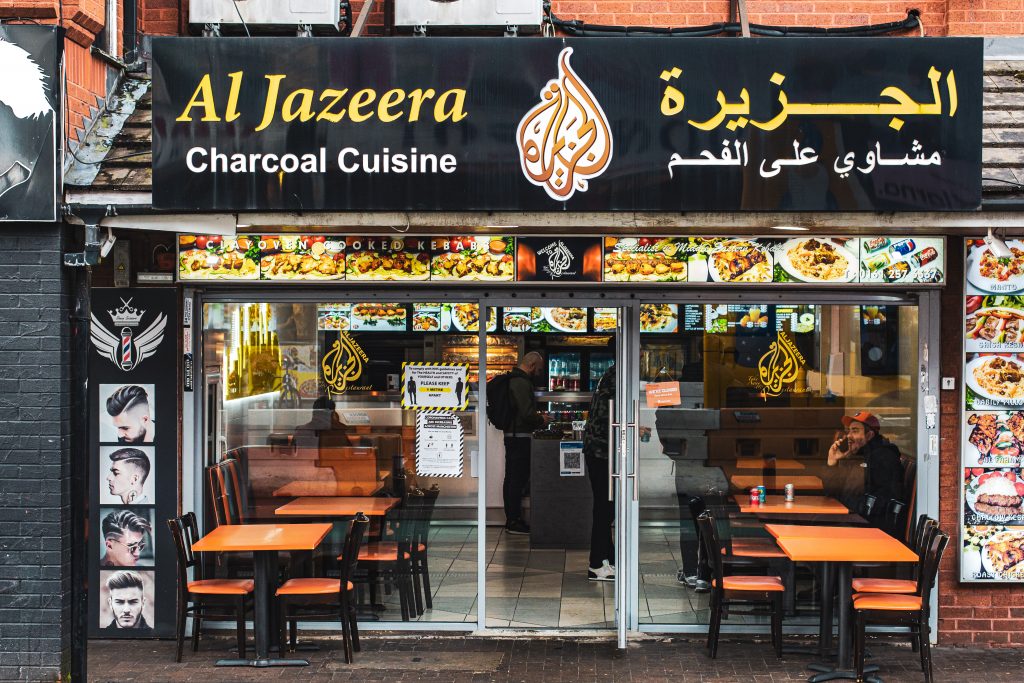

Our second stop sees us venture inside Al Jazeera, back across the road from Al Zain. Luke doubles down on the kobeda, while advising us to try the qabuli pulao, the national dish of Afghanistan.

From about four seconds after the food hits the table, it’s not difficult to figure out why the Afghanis flocked to this dish of delicate lamb (or beef) blanketed in a bed of steamed basmati rice, carrots and raisins cooked in a mouth watering broth. It disappears from sight in a matter of minutes, even with a Leviathan sized double kobeda sitting alongside it, crying out to be devoured.

As seems to be the norm for the area, the lamb is once again, in both dishes, expertly prepared, with the qabuli pulao’s shoulder cuts pulling away from the bone with the merest glance of contact from any cutlery, before melting magically in your mouth. The kobedas meanwhile pull apart just as easily along with the delightfully soft naan, which Luke declares is the best it’s ever been of all his visits to this establishment. The grins that were beaming stupidly from our respective faces across the road after our first few bites of Al Zain’s shawarma return almost instantly as we glug down the only acceptable drink in a venue such as this – An ice cold tin of Rubicon.

Magnificently, and rather inexplicably, the TV attached to the wall above our heads is screening a Madrid derby from what I guess is around 2004, given the kits and players on display. It’s a most welcome sense of nostalgia to distract from the chaos of the present day world outside.

The Best Art Happens With Cheap Rent

Back at Kurdistan Cafe, our appetites are slowing, as the effects of an afternoon full of shawarma, kobeda, naan and pulao begin to deliciously take their toll. The citrus notes of the sumac speckled lamb still encouraging us to gamely graze onwards as Luke regales us with the story of Rusholme’s recent Kurdish revolution.

“In the mid-2000’s Kurdish and Afghani places very slowly began to open and Kurdistan Cafe was really the beginning of that next moment in time in the journey of kebabs, post-Rusholme Chippy and Camel One. Kurdish people just revolutionised it all again. And it was cheap, all fresh and the big difference was they were using a wood grill where you had such a wonderful intensity of heat that was so hot, when the lamb kobeda go on there, you get this almost gnarly, crispy edge while in the middle it’s very, very soft.

“So Kurdistan Cafe really started this whole revolution, then opposite Jaffa there’s a place called Atlas, which is also run by Kurdish people and it’s a fusion of different cultures, so they have the Kurdish bread done in the tandoor, very light and they mix that with a shawarma, so it’s almost like a kebab wrap or whatever you want to call it. That ended up being a completely different hybrid of kebab, so on the one hand you had a classic kobeda, which are the Afghani style with the long breads, with the Kurdish kebabs which came with the traditional bread and the Kurdish-Lebanese fusion shawarma kebab.”

“The white middle classes completely missed this moment, because they didn’t want to come to areas like Rusholme, which they perceived to be a bit rougher. They didn’t realise that, although they weren’t aesthetically perhaps the most pleasing places to look at from the outside, there had been a quiet revolution and suddenly the most authentic and incredible kebabs had been created.”

This perceived rougher aesthetic is a large part of what makes Rusholme’s restaurant scene so invigorating. In a manner similar to the Bronx in New York, it’s an area that feels gentrification proof in a city almost universally adorned by it. No amount of modern renewal projects and regeneration are touching Wilmslow Road. The cheap rents allowing immigrant communities to thrive as business owners without constantly looking over their shoulders, worrying that an opportunistic landlord will hike them out the minute they notice queues outside the doors or a deluge of positive Tripadvisor reviews.

You cannot help but be charmed by Kurdistan Cafe, with it’s ‘60s wood panelled walls, chipped paint and fading framed photographs. The small assemblies of plastic flowers, tissue boxes and greasy spoon-esque bottles of HP sauce and sugar dispensers are impossible not to derive joy from. That’s before the food, which feeds the stomach and soul with equal levels of homely, heartwarming euphoria. It is here that Luke claims the ultimate Kurdish Kebab and Tandoor bread are to be found.

As Luke continues, while the ‘Curry Mile’ may be dead, what has replaced it is Manchester’s best kept secret.

“Out of the darkness of the defeat of the Curry Mile came the growth of something else, so the closing of one door led to the opening of another.

“The funny thing is it still feels like a bit of a secret, it’s so underground because everything’s been happening on the side streets of Rusholme, the main drag has become hookah bars and things of that nature while the white middle classes are going to places like Dishoom and Akbar’s. It’s become this sort of posh pastiche, but still very good food.

“It’s like music, you don’t get good music without cheap rent and that’s where the magic happens. The best art happens with cheap rent, it comes out of the darkness. Look at someone like Keith Haring, he came out of a period where New York was bust, there were fires everywhere, the city was riddled and bankrupt. Times Square was a no go after seven o’ clock, there was prostitution and destitution but out of that came the magic and I think, funnily enough, in Rusholme, while not as extreme as that, obviously, what came out of the lack of Curry Mile was cheap rent on the side roads so people could open up here and afford to sell food at a reasonable amount rather than going to Ancoats which, while I love all of that, these places are a different animal.

“Rusholme became a victim of it’s own success. It all became so top end, it lost it’s originality and authenticity and it became what I like to call a ‘baltiplex’. You’d go into places and they’d have four fucking sauces and that was it.

“This food is democratic, it’s soul food. The cost of a kebab here is five quid with breads and you get soup with it and it’s done right. In the city centre that’s costing you at least a tenner more. In Rusholme it’s never been as good and I think in Manchester things are always the best when there’s less hype. The moment it becomes a thing it kinda loses it’s way.”

Recalibrating After Armageddon

Of course, the all encompassing Covid-19 pandemic cannot be ignored while soaking in Rusholme’s Middle Eastern magic. Given the volume of restaurants and takeaways on Wilmslow Road that generate a resounding amount of their income in the small hours from the adjacent student population, the government’s stifling 10pm curfew, in addition to the impending second national lockdown, have surely done a significant number on trade, potentially leaving several businesses hanging in the balance over the next month or so.

And while none of us know for certain what terrors or triumphs are awaiting us, Luke has a positive outlook on how a post-Covid Rusholme will fare.

“Whatever happens and no matter how bad it gets, and it will get bad, it’ll be an almost Armageddon situation, I think what will come out of it will be food, art, literature and music surviving in ways people couldn’t even think of.

“I think after all this, people will turn off from influencers and EDM and focus more on the real deal and it’s the same with food. They’ll focus on quality, authenticity and value for money. They won’t want cheesy chips in a fuckin naan bread. It’ll go back to basics. This will recalibrate everything. I’m an optimist, I think there’ll be light out of the darkness.

“Naturally, a mixture of immigration and cheap rent will see things beyond the inner city walls going more this way. I don’t think you can stop it. Post covid there’ll be more of this, much more of this.”

A Far Cry From 3am Doner

This improvement in the authenticity and quality of kebabs is an evolution Luke has chronicled since falling head over heels with a kebab van doner in Sheffield in 1982 and it’s an evolution he believes holds a very promising future.

“The first kebab I ever had was 1982 in Sheffield, ‘Chubby’s & Popeye’s’. They were doners. Probably looking back it wasn’t very good but I absolutely loved it and fell in love with it.

“I actually sold my dad’s record collection for about four quid and bought two kebabs with it…I’ve got over it.

“But from having such a bad reputation in the ‘80s as being this awful drunken food at two in the morning, kebabs are now the healthiest, freshest peasant food you can eat in this country.

“My top five kebab places in Rusholme would be Kurdistan Cafe, Al Zain, Al Jazeera, Rusholme Chippy, Shireen Grill House on Rusholme Grove and Manchester Fresh Shawarma. So six, then, actually. If it was a desert island deal and it’s the last thing you’re ever gonna eat, though, I’d go Kurdistan Cafe.

“The whole Curry Mile is over and now you’ve got amazing Lebanese bakeries, Syrian places, great coffee, it’s a completely different place. Keep an eye out because there’s new places developing all the time. There’s one on the main street that looks amazing. It may be Syrian and it looks like they have a hog roast but it’s lamb going round. I’ve not had it yet but I will.”

We’ll be sure to join him when he does finally make his way there. In the meantime, with takeaway and deliveries our only option between 5th November and 2nd December, you couldn’t do much better than sending some of your custom Rusholme way and eating your way round the Middle East during lockdown two. Don’t forget the Rubicon, either.

Luke, and his rather brilliant daily updates, can be followed on Instagram HERE